Medieval Canterbury: Religious Centre & Pilgrimage Destination

Canterbury Cathedral - The Heart of Medieval Canterbury and Pilgrimage Destination

Canterbury's medieval history represents one of the most fascinating chapters in Kent's rich heritage, transforming from a modest settlement into a world-renowned pilgrimage destination and cultural hub. Following the Norman Conquest in 1066, Canterbury emerged as a pivotal religious centre whose influence extended across Europe, largely due to the dramatic martyrdom of Archbishop Thomas Becket in 1170 and the subsequent pilgrimage cult that developed around his shrine.

This comprehensive exploration delves into Canterbury's medieval development, examining how the city evolved architecturally, culturally, and spiritually from the Norman period through the late Middle Ages, leaving an indelible mark on English history and literature that continues to resonate today.

Canterbury After the Norman Conquest

When William the Conqueror seized England in 1066, Canterbury was already an established settlement with Anglo-Saxon roots and a cathedral dating back to 597 AD. The Norman period, however, brought significant changes to the cityscape and power structures within Canterbury.

Archbishop Lanfranc, appointed by William in 1070, embarked upon an ambitious rebuilding programme of Canterbury Cathedral, replacing the Anglo-Saxon structure with a much grander Norman design. This architectural transformation symbolised the broader cultural and political changes occurring across England as Norman influence took hold.

Key Developments in Norman Canterbury

The Norman reorganisation extended beyond religious buildings to include strengthening of Canterbury's city walls, establishment of new markets, and changes to land ownership recorded in the Domesday Book. The city's strategic importance grew as a centre of ecclesiastical power and a key stop on the route between London and the continent via Dover.

The Martyrdom of Thomas Becket

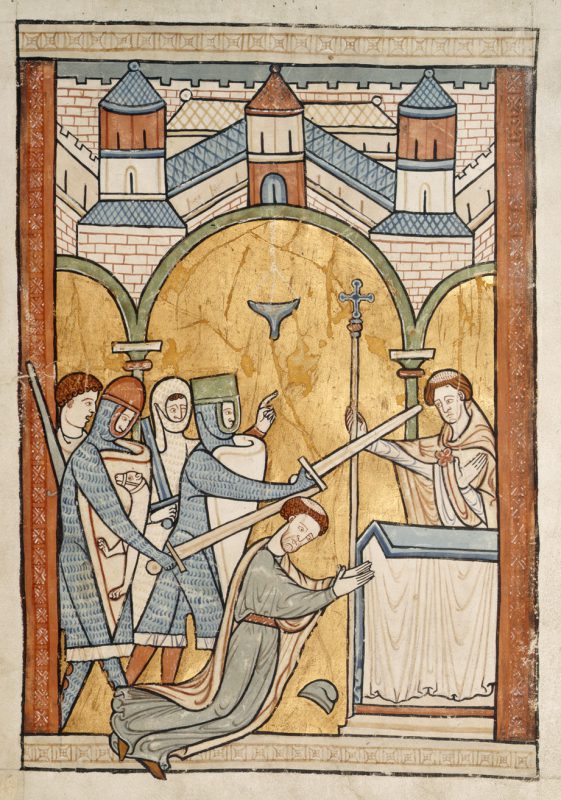

Medieval depiction of Thomas Becket's martyrdom - the event that transformed Canterbury's destiny

The single most transformative event in medieval Canterbury's history occurred on 29th December 1170, when Archbishop Thomas Becket was murdered in his own cathedral by four knights acting on what they believed to be the wishes of King Henry II. This shocking act of violence against a leading churchman in a sacred space would reshape Canterbury's destiny and establish it as one of medieval Europe's most important pilgrimage destinations.

Becket's conflict with Henry II stemmed from fundamental disagreements over the relationship between church and state. As Chancellor, Becket had been a close associate of the king, but upon becoming Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162, he emerged as a fierce defender of church privileges and independence from royal control. This shift led to increasingly bitter disputes, culminating in the famous utterance attributed to Henry II: "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?"

"What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?"

The four knightsâReginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy, and Richard le Bretonâinterpreted the king's angry words as a command. They travelled to Canterbury and confronted Becket in the cathedral. When he refused to flee or recant his positions, they struck him down with their swords, splitting his skull and spilling his brains onto the cathedral floor.

Word of the archbishop's martyrdom spread rapidly throughout Europe. Reports of miracles at Becket's tomb began almost immediately, and he was canonised remarkably quickly, just over two years after his death, in February 1173. The implications for Canterbury were profound and far-reaching.

Canterbury as a Pilgrimage Centre

Following Becket's canonisation, Canterbury rapidly developed into one of the most important pilgrimage destinations in Western Christendom. The journey to Canterbury to visit the shrine of St Thomas became known simply as "the pilgrimage," reflecting its pre-eminent status among English religious journeys.

Medieval illustration of pilgrims travelling to Canterbury

Pilgrimage to Canterbury offered multiple spiritual benefits for medieval Christians. Visitors could pray at the site of Becket's martyrdom in the north-west transept (thereafter known as "The Martyrdom"), visit his initial tomb in the crypt, and, after 1220, pray at his magnificent shrine in the newly built Trinity Chapel. Each location was believed to offer different spiritual benefits, and pilgrims would often visit all three.

The cult of St Thomas transformed Canterbury economically as well as spiritually. A vast infrastructure developed to support the influx of visitors from across Britain and continental Europe. Inns, hostels, and hospitals were established to accommodate pilgrims of different social classes. Shops selling pilgrim badges and souvenirs flourished along the main streets leading to the cathedral. These pilgrim badges, often depicting scenes from Becket's life or martyrdom, became prized possessions, believed to carry some of the saint's protective power.

Canterbury Pilgrim Souvenirs

- Ampullae (small lead flasks) containing Canterbury water, believed to be mixed with Becket's blood

- Pilgrim badges showing scenes from Becket's life and martyrdom

- Miniature swords representing the weapons that killed the archbishop

- Bells inscribed with Becket's name, thought to protect travellers

- "Head badges" representing the part of Becket's skull shattered during his murder

The economic impact of pilgrimage on Canterbury cannot be overstated. The city's prosperity in the 13th and 14th centuries was largely built on the pilgrim trade. Records suggest that in peak years, Canterbury might receive over 100,000 pilgrims, a remarkable number given the overall population of medieval England.

The Medieval Cathedral

The Canterbury Cathedral we see today was substantially shaped by the needs of the Becket pilgrimage cult. Following a devastating fire in 1174, just four years after Becket's death, master mason William of Sens was engaged to rebuild the cathedral's east end. His revolutionary design incorporated elements of the new Gothic style that had emerged in France, making Canterbury one of the first major Gothic buildings in England.

The most significant addition was the Trinity Chapel, completed in 1220, which would house Becket's shrine after his remains were translated from the crypt in a magnificent ceremony attended by King Henry III. The chapel featured soaring pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and innovative flying buttresses that allowed for larger windows, filling the space with coloured light.

The Trinity Chapel was designed specifically to accommodate large numbers of pilgrims, with an ambulatory allowing visitors to process around the shrine. The famous stained glass windows surrounding the chapel, known as the "Miracle Windows," depicted scenes of miraculous healings attributed to Becket, serving as visual narratives for pilgrims, many of whom would have been illiterate.

The shrine itself was a masterpiece of medieval craftsmanship, described by eyewitnesses as being covered in gold and studded with precious gems. A wooden canopy above it could be raised to reveal the gold-encased reliquary containing Becket's remains. The wealth poured into this shrine by grateful pilgrims and royal patrons made it one of the richest in Europe until its destruction during the Reformation.

Canterbury Tales and Literary Legacy

Canterbury's place in medieval culture was cemented by Geoffrey Chaucer's masterpiece, "The Canterbury Tales," written in the late 14th century. This collection of stories, told by a diverse group of pilgrims journeying from London to Canterbury, provides invaluable insights into the social fabric of late medieval England and the enduring importance of the Canterbury pilgrimage nearly two centuries after Becket's death.

"Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote...

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;

And specially from every shires ende

Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende,

The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke."

Chaucer's pilgrims represent a cross-section of medieval societyâfrom the noble Knight to the corrupt Pardoner, from the ribald Miller to the pious Parsonâoffering a vivid portrayal of the diverse types of people who would have visited Canterbury. Their tales, ranging from pious exempla to bawdy fabliaux, reflect the complex spiritual and social culture that developed around pilgrimage.

"The Canterbury Tales" also reveals how the practice of pilgrimage had evolved by the late 14th century. While some pilgrims were genuinely motivated by religious devotion, for others the journey had become as much a social occasion or holiday as a spiritual exercise. Chaucer's gentle satire suggests that by his time, pilgrimage could be undertaken with mixed motivationsâa combination of piety, sociability, curiosity, and pleasure-seeking.

Medieval City Life in Canterbury

Beyond the cathedral precinct, medieval Canterbury was a bustling urban centre with a complex social and economic life. The city was governed by a corporation of citizens who enjoyed considerable autonomy, with their own court and the right to collect certain taxes. The city walls, originally Roman but extensively repaired and modified during the medieval period, enclosed an area of approximately 130 acres.

Canterbury's street plan, which largely survives today, reflects its medieval development. The main thoroughfare of High Street/St Peter's Street follows the line of the old Roman road from London to Dover. Branching off this central spine were numerous smaller streets and lanes, often named for the trades concentrated there: Butchery Lane, Mercery Lane (for mercers selling fine textiles), and so on.

The city was home to numerous parish churchesâat least 18 by the late medieval periodâserving the spiritual needs of residents in different neighbourhoods. Most of these were small compared to the cathedral but nevertheless contained impressive examples of medieval art and architecture.

In addition to the cathedral, Canterbury had several important religious houses. St Augustine's Abbey, founded in the 6th century but substantially rebuilt in the Norman period, was one of England's most important Benedictine monasteries. The Dominican friary (Blackfriars), established in 1237, and the Franciscan friary (Greyfriars), founded in 1225, brought the new mendicant orders into the city, adding to its spiritual landscape.

Commerce was central to Canterbury's life. Regular markets were held in designated areas like the Buttermarket, while specialised trades were often concentrated in specific streets or quarters. The city was known for cloth production, leatherworking, and, naturally, industries catering to pilgrims, such as badge-making and inn-keeping. Canterbury's proximity to London and the continent made it an important node in trading networks.

Canterbury's medieval population is estimated to have reached around 10,000 at its peak in the early 14th century, making it one of England's larger provincial cities. Like most medieval urban centres, it suffered significantly from the Black Death in 1348-49, losing perhaps a third of its population. Recovery was slow but steady, and by the 15th century, the city had regained much of its prosperity.

Late Medieval Canterbury

The 14th and 15th centuries brought both continuity and change to Canterbury. The Peasants' Revolt of 1381 briefly threatened the city when rebels from Kent, led by Wat Tyler, directed some of their anger toward the cathedral and its monks, though the damage was limited. The political instability of the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487) had relatively little direct impact on Canterbury, which remained primarily focused on its religious and commercial functions.

Architecturally, Canterbury continued to evolve during this period. The cathedral's distinctive central tower, known as Bell Harry Tower, was rebuilt between 1494 and 1504, providing the final dramatic element to the building's skyline. The city walls were strengthened, and the Westgateâwhich still stands today as Canterbury's most impressive medieval secular structureâwas rebuilt in the 1380s.

Spiritually, while the Becket cult remained central to Canterbury's identity, the later medieval period saw growing religious diversity and, in some quarters, calls for reform. Lollard influences, representing early stirrings of what would later become Protestant ideology, can be detected in Kent from the late 14th century, though Canterbury itself, dominated by its powerful ecclesiastical institutions, remained largely orthodox.

By the early 16th century, on the eve of the Reformation that would transform England's religious landscape, Canterbury stood as a mature medieval city. Its street pattern was firmly established, its major buildings completed, and its identity as England's premier pilgrimage destination seemingly secure. The traumatic changes of the Reformation eraâparticularly the destruction of Becket's shrine in 1538 on the orders of Henry VIIIâwould dramatically alter Canterbury's spiritual and economic foundations, marking the effective end of its medieval golden age.

Legacy and Preservation

Today's visitors to Canterbury encounter a remarkably well-preserved medieval cityscape. Despite bombing during the Second World War and the pressures of modern development, Canterbury retains substantial portions of its medieval fabric. The cathedral, though modified over the centuries, remains one of the finest examples of medieval ecclesiastical architecture in Britain. The city walls, though incomplete, offer tangible links to the medieval past, as do surviving medieval buildings like Eastbridge Hospital, which once accommodated poor pilgrims.

Archaeological investigations continue to enhance our understanding of medieval Canterbury. Excavations have revealed details of everyday life, trade networks, and material culture that complement the documentary record. The physical evidence of pilgrim badges, pottery, and other artefacts helps bring the medieval city to life in ways that texts alone cannot.

Canterbury's medieval heritage has been recognised internationally through its UNESCO World Heritage Site designation, which encompasses the cathedral, St Augustine's Abbey, and St Martin's Church. This designation acknowledges the exceptional historical and cultural significance of Canterbury as a centre of medieval Christianity in England.

The legacy of medieval Canterbury extends far beyond the physical remains. Through Chaucer's immortal "Canterbury Tales," the city and its pilgrimage tradition have become embedded in English literature and cultural consciousness. The story of Becket's martyrdom continues to resonate as a powerful narrative about the conflict between church and state, while the concept of pilgrimageâthough transformedâremains relevant in both religious and secular contexts.

Related Resources

To explore Kent's rich medieval heritage further, we recommend visiting the following pages:

- Anglo-Saxon Heritage - Understand the foundations upon which medieval Canterbury was built

- Tudor Kent - Discover how the Reformation transformed Canterbury's medieval religious landscape

- Kent Churches & Cathedrals - Explore other magnificent religious buildings across the county

- Kent Castles & Fortifications - Learn about the defensive structures that protected medieval Kent

Canterbury's medieval history represents a fascinating intersection of religion, politics, architecture, and culture. From the Norman rebuilding to the development of the Becket cult, from Chaucer's pilgrims to the city's thriving markets, medieval Canterbury offers a window into a world both distant and strangely familiarâa world whose physical and cultural legacy continues to shape our understanding of England's past.